Ten Across | Environment

Managing groundwater on the US-Mexico border is challenging—but vital

Photo credit: Vedrana Filipović for Unsplash

The amount of water in the more than two dozen viable aquifers shared by the two countries is unknown, and few regulations guide their use

Editor’s note: This article is part of a collaboration between APM Research Lab and the Ten Across initiative, housed at Arizona State University.

by Maya Chari | September 12, 2024

Constellation Brands, a U.S.-based beverage company, announced in 2016 that they would begin construction on a new brewery in Mexicali, Baja California. Constellation already operated two factories in Mexico, producing beers like Corona and Modelo for American consumers.

Almost immediately, the project met with opposition from local farmers and other residents, who feared that the brewery would deplete the region’s scarce water supply. The city of Mexicali depends not only on the Colorado River, but on the Mexicali Valley Aquifer, which Mexico’s National Water Commission has declared overexploited.

The Mexicali Valley Aquifer is one of over two dozen aquifers that spans the U.S.-Mexico border.

What are transboundary aquifers, and why are they important?

Aquifers are subterranean bodies of rock or sediment saturated with water, created when water seeps through permeable soil. Aquifer volume is recharged by precipitation, snowmelt, or discharge from a river, though the rates of recharge vary greatly based on factors including depth and surface permeability.

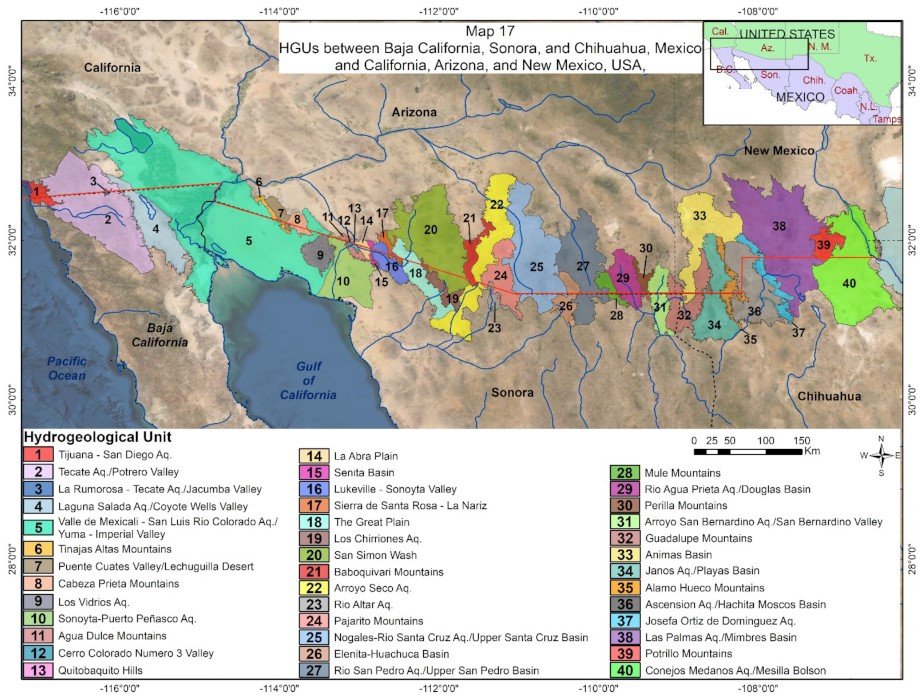

A transboundary aquifer is one that crosses an international border. While different studies have come up with various numbers, the most recent and comprehensive study has estimated that there are 72 hydrogeological units (HGUs), or potential aquifers, in the U.S.-Mexico border region. At least 28 have the hydrogeological features and water quality necessary to serve as aquifers for human use.

Image Credit: Rosario Sánchez and Laura Rodriguez, Water Journal, October 21, 2021

Water in aquifers can be accessed through drilling and pumping wells. Globally, aquifers provide 50% of drinking water and 40% of water used for irrigation.

Eighty percent of water demand in the U.S.-Mexico border region, defined as the 100 kilometers on either side of the border, comes from agriculture. Another 14%-16% of water used in the region goes to municipal and industrial purposes, meaning that it is used by households or businesses. Another 2% is used to produce thermoelectric power.

Overall, water use in the border region is more similar to water use in Mexico than in the United States as a whole.

Globally, groundwater is under stress, and the North American Southwest is no exception

Jay Famiglietti, a professor of global futures at Arizona State University, has been using satellites to track change in freshwater availability and groundwater supplies for the past 25 years. In that time, his research has shown that groundwater supplies, many of which underlie major agricultural production, have declined significantly.

The Southwest U.S. and Northern Mexico are under particular stress. The naturally arid region faces a decades-long drought, a booming population and an explosion in industry.

The rise of maquiladoras — factories located in Northern Mexico, typically close to the border, but owned by U.S. companies and used to assemble goods primarily for export — add to demand for groundwater. So does beer production in the Mexican states of Coahuila and Sonora. On the Texan side of the border, hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, for oil exerts pressure on aquifers. Groundwater is also threatened when recharge areas are paved, which prevents precipitation from refilling aquifers.

In Mexico, water availability has declined across the country, most sharply in the northern regions, where aquifers are the main source of water. A 2021 study suggested that water from Mexico-U.S. transboundary aquifers is being extracted approximately 14% faster than it is recharged.

Why don’t we know how much groundwater we have?

Although it’s known that groundwater supplies are declining, it’s unknown how much water is currently stored in aquifers. Aquifer volume cannot be precisely measured, only estimated, and accurate estimates require costly research.

“I’ve been screaming into the wind about this for 15, 20 years now,” said Famiglietti. “We don’t know how much groundwater we have, which seems ridiculous. And the reason we don’t know is because it costs money [to find out].”

Rosario Sánchez, a research scientist at the Texas Water Resources Institute who has worked extensively on the Transboundary Aquifer Assessment Program (TAAP), identified another factor. “It’s very convenient, not knowing much,” she said. “We live on the assumption that water — especially groundwater — is infinite.”

What laws and treaties govern transboundary aquifer use?

In Mexico, all groundwater technically belongs to the government, which issues permits allowing use by households and businesses. In the United States, groundwater management strategy varies by state.

In Arizona, the 1980 Groundwater Management Code established active management areas and irrigation non-expansion areas in several areas in the state. In these areas, water use is regulated and must be reported. Outside of these areas, however, groundwater use is minimally managed. Texas and California have similar systems, in which groundwater use is only regulated in designated groundwater conservation districts or adjudicated basins, respectively. Outside of these areas, users are not even required to file any reports on the amount of water that they extract.

In New Mexico, however, both groundwater and surface water use are centrally managed through the Office of the State Engineer. The state has also established a collaborative groundwater monitoring network, intended to help users “track changes and make informed decisions” about water management.

In 2006, Congress passed the U.S.-Mexico Transboundary Aquifer Assessment Act, which established the Transboundary Aquifer Assessment Program (TAAP), a binational effort to assess the aquifers on the border. TAAP is the source of the latest estimates on the number and quality of transboundary aquifers.

In general, transboundary water use between the U.S. and Mexico has been governed by the 1944 Water Treaty, which allocated a certain amount of transboundary water supply to each country. It also established the International Boundary and Water Commission (IBWC), which is tasked with allocating, managing and monitoring water supplies. IBWC decisions are recorded as “minutes,” which can then be ratified by the governments of each country.

While the original treaty does not mention groundwater, minute 242, ratified in 1973, explicitly gave the IBWC authority over groundwater. It also established regulations around groundwater pumping near San Luis, a city on the Arizona-Sonora border, which are still in place.

Minute 242 was meant to be a stopgap agreement, governing groundwater in one area “pending the conclusion by the Governments of the United States and Mexico of a comprehensive agreement on groundwater in the border areas.” But that comprehensive agreement never materialized.

“It’s been languishing for 50 years,” said Stephen Mumme, a political science professor at Colorado State University who specializes in transboundary water politics. Outside of the San Luis area, there are still few restrictions on pumping in the region.

In a 2022 report, Sánchez and colleague Laura Rodriguez warned that without proper regulation and protection, groundwater “has potential to become a security threat to the border region.”

Whiskey is for drinking, water is for litigation

To describe the impact of water in binational politics, Mumme referenced a saying sometimes attributed to Mark Twain: “Whiskey is for drinking, water is for fighting over.”

The last thirty years have seen two major U.S.-Mexico conflicts over water. The 1944 treaty allows for one country to use more water than allocated in cases of “extraordinary drought” in one country and an “abundant supply of water” in another. In 1999, Mexico failed to deliver the amount of water required by the treaty, claiming extraordinary drought.

Farmers and irrigation districts in Texas threatened legal action under chapter 11 of the North American Fair Trade Agreement (NAFTA), citing satellite photography of water supplies and agriculture in Mexico. The U.S. and Mexico eventually came to an agreement that Mexico would gradually pay its water debt to the U.S. The debt was discharged in 2016.

In 2005, the U.S. unilaterally pursued a project to pave a section of the All-American Canal, an aqueduct in southeastern California. Paving the previously earthen canal prevented water from seeping to surrounding ecosystems and from recharging aquifers, including the Mexicali Valley aquifer. Many Mexican farmers relied upon these aquifers for their water supply. A binational coalition brought these concerns before the U.S. Ninth Circuit Federal District Court, but they were dismissed, and the lining of the canal continued.

Cross-border water disputes are not limited to national borders. Texas has sued New Mexico for “excessive” groundwater pumping, which it argued depleted Texas’s share of Rio Grande water. That case is ongoing, after the Supreme Court rejected a proposed settlement in June.

Holly Brause, an anthropologist studying transboundary water at New Mexico State University, noted that the lawsuit has impeded potential transboundary collaboration in the state. “Mexico doesn’t want to be drawn into a lawsuit between Texas and New Mexico,” she said.

Agricultural interests have also used lawsuits to resist attempts at managing groundwater. In California, for instance, growers are suing the state over a requirement that they measure and report the amount of groundwater they use.

What would a sound management strategy look like?

According to Famiglietti, there are two crucial components of groundwater preservation: measurement and management. “We need to find out how much groundwater we have, and how much is renewable. From there, different regions can assemble stakeholders to work out a bottom-up sustainability plan, and one that looks to future generations.”

Brause has interviewed dozens of farmers on both sides of the New Mexico/Chihuahua border about the region’s water futures. She noted that “farmers are really scared that someone’s going to make a decision in Santa Fe or in Washington, DC [that] will wipe out their water rights. So their opinions are on the defensive. Whereas if they felt like scientists and politicians were really paying attention to them and what their needs are, and taking into account their livelihoods and traditions and culture and were finding that valuable publicly, I think that they would be much more willing to come to the table and collaborate on finding solutions.”

The 1944 Water Treaty and its amending minutes have also failed to consult with or adequately address the needs of the Cocopah Tribe, who also rely on surface and groundwater in the border region.

In their report, Sánchez and Rodriguez suggested national acknowledgement of the 28 transboundary aquifers as a first step towards binational discussion about shared management. That could mean a binational framework customized and implemented on a local level. The United Nations has developed a model for the management of transboundary groundwater, which could be adapted to suit regional needs.

In Mexicali, after two years of organized resistance, the Mexican government held a plebiscite in which 76.1% of voters came out against the brewery. The project was scrapped.

“Groundwater is very attached to individuals and communities,” said Sánchez.

She pointed to the Franco-Swiss Genevese Aquifer as a model of successful transboundary aquifer governance. With approval from both federal governments, decisions about withdrawals from the Genevese aquifer are made by local communities on both sides of the border.

“Rather than federal, macro-level institutions making decisions, they left it to the locals. Because they know better, because they rely on that.”

The author would like to thank Sharon B. Megdal of the University of Arizona’s Water Resources Research Center and Dorina Murgulet of the Center for Water Supply Studies at Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi for valuable background information that helped to inform this story.

Note: An earlier version of this article misidentified Holly Brause's affiliation as University of New Mexico. It now correctly lists her affiliation as New Mexico State University.