Looking beyond race: Americans' heritage reflects the globe

Photo by Samantha Gades on Unsplash.

by Andi Egbert, Sr. Research Associate

Looking beyond race

Americans' heritage reflects the globe

Americans are deeply curious about the origins of their 326 million neighbors—including their leaders.

Yes, Barack Obama was our nation’s “first Black president,” but that description is incomplete. Due to his African-born father, he has Kenyan heritage, along with 87,000 other American residents, as our new Roots Beyond Race project reveals. And his White, Kansas-born mother also gave him European heritage, as nearly 2.2 million Black Americans claim. First Lady Melania Trump has ties to present-day Slovenia, as do 179,000 other U.S. residents.

Roots Beyond Race reveals the complex, overlapping, and fascinating collective heritage of Americans, including its Indigenous populations. Two interactive tools allow users to explore data on 198 heritage groups, revealing a degree of detail that we seldom see. You could easily spend an afternoon asking interesting questions of the data:

Which state has the most Kurdish heritage residents? (Tennessee)

Which state has the highest share of people with Cambodian background? (Rhode Island)

What percent of the nearly 38 million Americans with Mexican heritage were born in the U.S.? (70%)

What is the largest tribal affiliation among single-race Indigenous people? (Navajo)

What is the most common Latino group in Maryland? (Salvadoran)

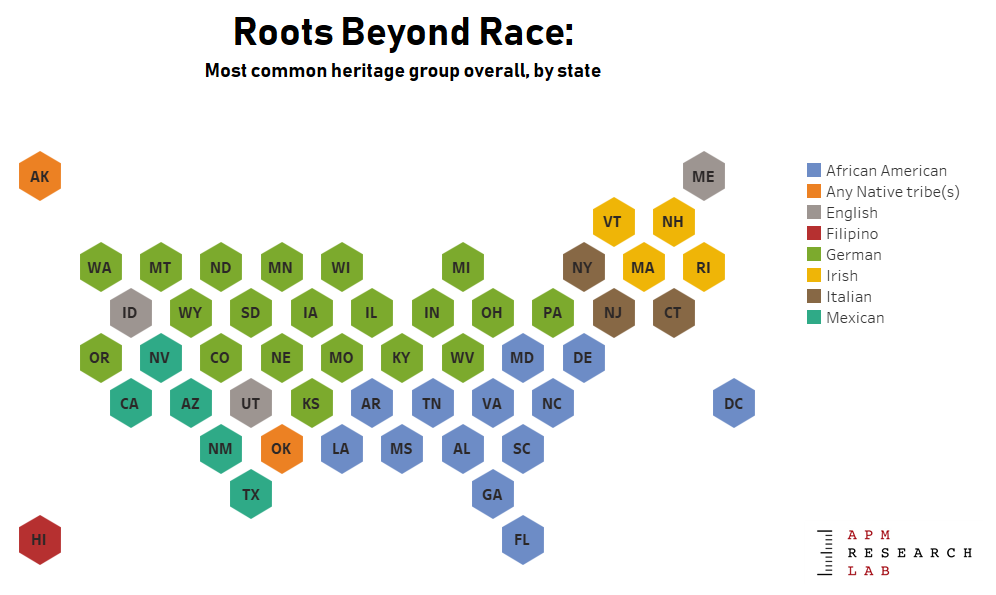

Roots Beyond Race also reveals that German heritage is the most common background in the United States overall, as well as in 20 states. (In Wisconsin, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa, and Minnesota, more than 3 in 10 residents have German roots, leading the nation.) African American is the most common heritage in 12 states and the District of Columbia. Mexican is the most common background in five states, Irish in four, Italian and English in three apiece.

In Alaska and Oklahoma, “any Native tribe” is the most cited background, while Filipino is most common in one state alone: Hawaii. Were you surprised that native Hawaiians were not the most common heritage in Hawaii? I was. More residents of Hawaii claim Filipino or Japanese heritage than Hawaiian.

Fortunately, Roots Beyond Race can now stand in place of our guesswork about our neighbors, teaching us how differently our states’ populations are constituted, and how waves of immigration (and sometimes subsequent migration) right up to the present have patterned the map differently: the heavily Scandinavian presence in the Midwest, the Irish influence in the Northeast, or the Mexican heritage in the Southwest.

It is essential to reflect on the composition of our race labels. Doing so will help us to better dismantle the inequities that plague our nation.

Another valuable feature of the Roots Beyond Race project is a cautionary tale about the shortcomings of basic racial labels. Yes, Americans are White, Black, Asian, Pacific Islander, Latino, and often a combination of those labels. And as a researcher, disaggregating data by race is absolutely essential to unveiling the glaring racial inequities that exist in health care, housing, education, employment, and our criminal justice system.

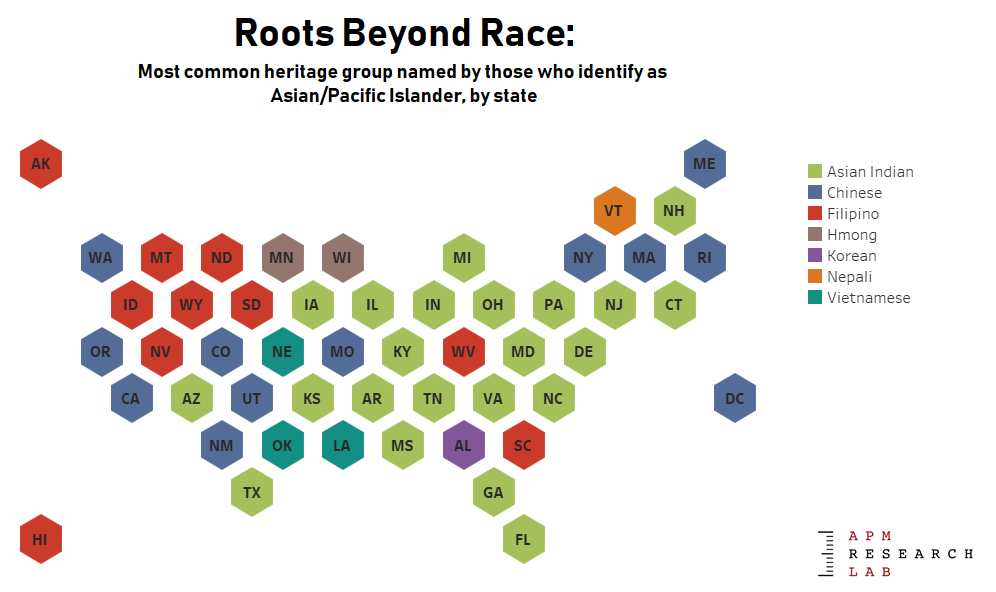

But we cannot stop there. We must teach ourselves how basic racial labels comprise very different populations depending on geography. Take for example our Asian/Pacific Islander population: In Minnesota, the largest heritage groups under that label are Hmong and Asian Indian. In California, it’s Chinese and Filipino. In Nebraska, it’s Vietnamese and Nepali. Furthermore, the same heritage group may have varying degrees of immigrants versus longstanding American residents among them: While 82% of Hawaii’s Chinese population was born in the United States, only 33% of Chinese New Yorkers were (as the tooltip in Roots Beyond Race shows).

When we consider, for example, “how Asians are doing” (by any social or economic indicator) or “what Latinos prefer” (whether at the ballot box or in the marketplace) we must remember that these broad racial and ethnic labels encompass wide-ranging diversity. Underneath each label are populations whose culture (visible and invisible), customs, languages, assets, needs, and arrival stories—especially if they are refugees or asylees who fled persecution and violence before arriving in the United States—differ greatly.

It is essential that we reflect on the composition of our race labels and deepen our understanding of the roots that go beyond race. Doing so will help us dismantle the inequities that continue to plague our nation. And it will also help us better appreciate and integrate the cultural assets that each group brings to America, this country with a truly kaleidoscopic heritage.

-Andi (@DataANDInfo)

EXPLORE ALL THE DATA IN ROOTS BEYOND RACE NOW.

Reactions? Please email us your thoughts or join the conversation on Twitter or Facebook.