POINTS OF REFERENCE

Where the U.S. now stands with Monkeypox and how we got here

by Terrence Fraser | November 2, 2022

The United States has had the largest monkeypox outbreak in the world in 2022. This article uses public health data to track the severity of the global outbreak and the urgency of the U.S. government’s response. Experts say the U.S. public health system needs a reset.

WHAT ARE THE ORIGINS AND SYMPTOMS OF MONKEYPOX?

Monkeypox has been known to science since the 1950s; and in 1970, the first human case of monkeypox was identified in a child in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

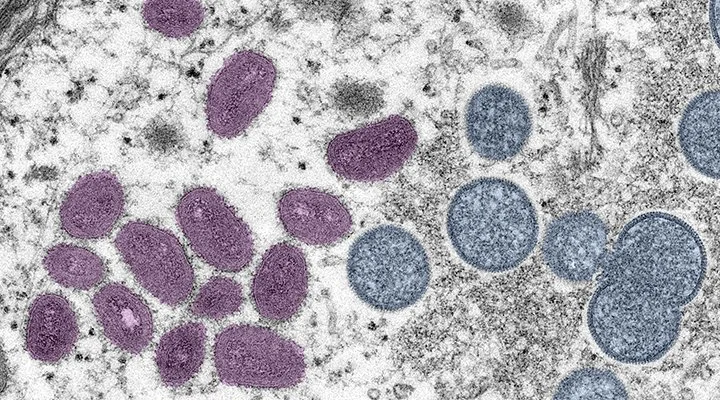

Monkeypox is in the same viral family as smallpox—a disease which had spread for at least 3,000 years until its eradication in 1980. Monkeypox symptoms are like smallpox, but far milder, according to Dr. Stephen Morse, professor of epidemiology at Columbia University Medical Center.

“Smallpox was a human virus that was very well adapted to person-to-person transmission, before it was eradicated, and killed about 30% of the people it infected. Many of those who survived had blindness or disfiguring pox marks,” Morse said. On the other hand, with monkeypox, “one might have one or two lesions; there might be a rash, but in general, one does not have the very severe effects that you saw with smallpox.”

Besides the appearance of a rash, blisters, or pimple-like bumps on the face, hands, genitalia or other parts of the body, other possible symptoms of monkeypox include a fever, swollen lymph nodes and flu-like symptoms, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

HOW DOES MONKEYPOX SPREAD?

Monkeypox has traditionally spread to humans through contact with infected animals; and human outbreaks have usually occurred in Central and West African countries, especially among people who live near forests and are more likely to encounter animals with the virus.

However, outbreaks of monkeypox in Africa have accelerated and spread to new areas over time. For instance, over the past several decades, Nigeria had very rarely reported monkeypox cases. But the virus became a problem for the West African country in 2017, when it reported its first major monkeypox outbreak.

“We had a 38-year gap before we had the outbreak that occurred in 2017,” said Dr. Dimie Ogoina, professor of medicine and infectious diseases at Niger Delta University. “We had three cases before then—two cases in 1971 and one case in 1978.”

Ogoina was the doctor who diagnosed the first monkeypox case in Nigeria in nearly 40 years; he also identified that the virus’s mode of transmission may have changed. During the 2017 outbreak, Ogoina noticed that 80% of his patients with monkeypox had “unusual” ulcers on their genitals in addition to genital rash.

“That's what led us to suspect that perhaps there’s a role of sexual contact in the transmission of monkeypox,” Ogoina said.

In October, U.S. Army scientists published a study which found monkeypox virus in the testes of primates. While the authors cautioned that this study may not fully reflect monkeypox in humans, the finding still adds to growing evidence that sex is a potential route for human-to-human monkeypox transmission.

In the case of the outbreak in Nigeria, however, the primary mode of monkeypox transmission is unclear, with 65% of monkeypox cases in the country being of unknown origin, according to Ogoina. The Nigerian health system is decentralized and “still very weak,” Ogoina said, and the collection and tracking of public health data in the country is “still a significant issue.”

There are two strains (or clades) of the monkeypox virus and the viral strain of monkeypox circulating in Nigeria is called clade II. Clade II has primarily spread in West Africa, including in Nigeria and eastern Cameroon—and it's also responsible for this year’s global outbreak in Europe and the Americas. Clade I only spreads in Central Africa, in countries like Democratic Republic of the Congo and Sudan.

Humans can contract monkeypox clade II either through contact with infected animals or from other humans with the virus. Humans spread the virus to one another through sex or other close, prolonged, skin-to-skin contact, or by touching an infected person’s clothes or bedding.

Clade I, on the other hand, is only documented as having spread from animals to humans. The World Health Organization states, “eating inadequately cooked meat and other animal products of infected animals is a possible risk factor” for animal-to-human transmission of monkeypox.

While the clades’ origins are currently unknown, Morse hypothesizes that animals carrying the two branches of monkeypox may have been geographically isolated, causing them to evolve differently over time.

“We see this with a lot of viruses,” said Morse. “If you have two very closely related viruses in two different parts of the world, you can see fingerprints of their geographic origin or relationship with one species of natural hosts rather than another. That kind of diversification naturally occurs over time.”

With regards to sustained human-to-human transmission, Morse says there isn’t enough scientific evidence to say whether there’s a more human-adapted mutation of the monkeypox virus or whether conditions were different, favoring monkeypox spreading more widely.

As a DNA virus, monkeypox mutates much less frequently than RNA viruses such as COVID-19 and HIV. However, Morse noted that the more chances the virus gets to infect humans, the more likely a variant could evolve to sustain itself in humans.

WHO IS THE GLOBAL OUTBREAK IMPACTING?

Clade II of the monkeypox virus, which is responsible for the 2022 global outbreak, has infected more men than women, regardless of its geography.

“In West Africa and in the global North, most of those being infected are younger adults between the ages of 20 to 40 years old,” said Ogoina. “In Nigeria, 70 to 75% of the cases are in males. But if you look at the global North, 90-something percent of those infected are male.”

Outside of the continent of Africa, the monkeypox outbreak is primarily impacting gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (MSM), with 80 to 100% of cases being reported within this group throughout the global outbreak, according to data compiled by the World Health Organization.

“In this outbreak that's occurring outside of endemic countries, the virus has found itself in a sexual network—and the at-risk group for this outbreak happens to be men who have sex with men,” said Dr. Amesh Adalja, senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. “We've not seen sustained transmission outside of that group.”

But even though men who have sex with men are experiencing the greatest number of monkeypox cases right now, this group is not inherently predisposed to contracting the virus, said Dr. Dustin Duncan, associate professor of epidemiology at Columbia Mailman School of Public Health.

“I get the sense that people may think that monkeypox is just a gay disease. Which of course it’s not,” Duncan said. Duncan added, however, that once an infectious disease has spread within a particular group, it can be easier for it to stay within that group rather than spread to new populations.

Public health experts believe the virus took on global dimensions in Western Europe, through events in which queer men had multiple sex partners in a short period of time.

Former head of the World Health Organization emergencies department, Dr. David Heymann, told The Associated Press in May that the global monkeypox outbreak was "a random event" likely spread through sex at raves in Spain and Belgium.

Events like raves and festivals can more easily can spread infectious diseases within the global sexual network of men who have sex with men, said Adalja. “You might have individuals who have multiple sexual contacts within a weekend. That's going to be very advantageous if you are a pathogen that spreads through close, sexually associated contact.”

WHAT NATIONS HAVE THE HIGHEST LEVELS?

So far in 2022, the United States has reported over 28,000 confirmed monkeypox cases, a figure far surpassing all other countries and representing 37% of all cases documented globally this year.

From June to mid-July, most new monkeypox cases outside of Africa were concentrated in Europe—over 1,900 cases per week were reported between June 20th and July 18th. On July 23rd, the World Health Organization declared the global outbreak a public health emergency in response to this rise in cases.

Then, in late July and early August, a few weeks after Europe’s peak in cases, cases in the United States also began rising sharply. The U.S. outbreak went from less than 100 cases per week during the week of June 20th to over 1,100 cases per week on July 18th. By July 25th, monkeypox cases in the U.S. surpassed all of Europe at a rate of 2,300 cases per week. U.S. weekly cases finally peaked in mid-August, with over 3,300 cases per week reported on August 15th.

APM Research Lab analysis also looked specifically at countries with at least 100 confirmed monkeypox cases this year and compared their total infections with their population size.

While the U.S. ranks number one in the world in total monkeypox cases, it ranks fourth in terms of its rate of monkeypox infections—in part due to its larger population size. Spain, Portugal and Peru all have infection rates higher than the United States’ rate of 8.5 monkeypox cases per 100,000.

Spain's population is about 47 million and the Western European country has reported over 7,300 total cases this year—that’s 9.5% of all monkeypox cases worldwide and 15.4 confirmed monkeypox cases per 100,000 persons.

Portugal has the second highest rate. With a population of about 10.3 million, this country bordering Spain has reported about 940 monkeypox cases. That’s an infection rate of 9.2 cases per 100,000 persons, but only 1.2% of global cases.

In Peru, monkeypox cases have skyrocketed within the past month. Infections have jumped by 400 cases in October alone, increasing the South American country’s rate of monkeypox infection from 7.8 cases per 100,000 persons to 9.2 cases per 100,000 during this time period. With a population of about 33 million people and over 3,000 confirmed monkeypox cases, Peru now ranks third highest in the world in terms of its rate of monkeypox infection.

While countries in West and Central Africa haven’t made this list, cases in these regions are likely much higher than data on confirmed and even suspected cases of monkeypox suggest.

According to data from the African Centers for Disease Control, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), there have been over 4,000 suspected monkeypox cases this year, but only about 200 cases have been confirmed. If we take the data at face value, however, DRC with its population of at least 90 million people, has a monkeypox infection rate of 4.8 cases per 100,000 persons. In Nigeria, 550 cases have been confirmed, but nearly 1,300 more are suspected. Taking the confirmed and suspected numbers together, Nigeria with a population of nearly 210 million people has a monkeypox infection rate of less than 1 case per 100,000.

But according to Ogoina, many cases of monkeypox in Nigeria and the DRC are not being detected.

“We’re working blindly,” Ogoina said of public health efforts to address monkeypox in his home country of Nigeria. "If you don't detect all your cases, you can't understand the disease and you can't respond appropriately.” Ogoina also added that the DRC needs further support from the international community to address the outbreak in the country.

WHERE IS IT CONCENTRATED IN THE U.S.?

Monkeypox has spread primarily throughout cities, said Dan Royles, associate professor of history at Florida International University.

“We are seeing the density of monkeypox cases in the U.S. in cities because that's where sexual networks of men who have sex with men are the densest. That's where you have bars and bath houses, and more opportunities to have sexual contact,” Royles said, adding that many openly queer men leave home to find community within cities.

“The normative expectation that goes with coming out is that if you're not in the cities, then you go to a city, possibly, the nearest big city to you and find the other gay people there.”

Among U.S. cities, New York has the highest number of cases, with over 3,700 total monkeypox cases citywide (13% of the national total).

But Miami, Florida has had the highest monkeypox infection rate among selected major cities this year. Miami has a total of about 860 confirmed monkeypox cases—3% of the over 28,000 total cases reported nationally. With a population of less than 450,000 people, Miami’s monkeypox infection rate is 195 cases per 100,000 persons. Atlanta, Georgia comes in second with a monkeypox infection rate of 155 cases per 100,000 persons. Atlanta has a population of about 500,000 people and over 770 confirmed monkeypox cases in total—which is 2.8% of all cases reported nationally.

On a statewide level, California—the most populous state in the country—also has the greatest number of cases, followed by New York State, Florida and Texas. In order of severity, the states with the highest percentage of their population infected with monkeypox are New York, Georgia and California.

HOW DID THE U.S. RESPOND?

The primary vaccine used during this year’s outbreak is called Jynneos. Jynneos was developed by the U.S. government and in 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the vaccine for the prevention of monkeypox (and smallpox).

However, according to reporting by The New York Times, fewer than 2,400 doses were available for use at the start of the national monkeypox outbreak. That’s because the federal government failed to replace 20 million doses of the Jynneos vaccine that expired over the past decade. As a result, there weren’t enough vaccines left over to protect the population of sexually active queer men at risk of getting monkeypox as the virus spread throughout the U.S.

“The expiration occurred because most people didn't think of monkeypox as a threat,” said Adalja. He added, “The Jynneos vaccine happens to work against monkeypox, but it was designed as an alternative vaccine for smallpox.”

According to an archived version of the U.S. Health and Human Services website, the federal preparedness agency first distributed Jynneos vaccines to states on May 21st, days after the first documented U.S. case of monkeypox in Boston this year.

While the number of vials HHS initially distributed to states is unclear, on June 28th the federal agency announced it would be making 56,000 vials of the vaccine immediately available. On July 6th, however, data from the agency’s department for preparedness and response showed only 42,000 vials had been distributed to states.

Throughout the outbreak, and especially early on, demand for the vaccine far outpaced supply across the country. In New York City, where the country’s first major outbreak occurred, appointments for the initial 2,500 doses of the vaccine were booked in minutes. San Francisco Health Department Director, Dr. Grant Colfax, said in a July press conference that the city was “literally begging our federal partners to provide more vaccine.”

But by August 8th, HHS data showed that over 600,000 Jynneos vials had been distributed to states. And on August 9th, with cases peaking across the country, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued emergency approval for intradermal Jynneos vaccine shots—allowing one vial of the drug to be used for five vaccine doses rather than one.

But experts say that was too late.

“The vaccines came really late,” said Royles, who argued that shots should have been accessible to queer men before Pride—an annual celebration starting in June which brings together the LGBTQ+ community in large numbers.

"There was some slowness to act on the part of the federal government in a critical early phase of the outbreak that could have made a big difference if they had done more,” Royles added.

As of June 19th—just days before a major Pride weekend in New York City—less than 500 people had gotten their first dose of the vaccine.

However, queer men continued getting vaccinated throughout Pride season. More than 116,000 doses had been administered by the end of July. By the end of August, the number of administered Jynneos shots had reached 600,000 and by mid-October, individuals across the country had received nearly one million first and second doses.

An approved treatment following a monkeypox infection was not available during this year’s national outbreak, however. An anti-viral treatment called tecovirimat, or TPOXX, was approved by the FDA in 2018 for the treatment of smallpox, but not for monkeypox. According to the CDC, the treatment has been effective against smallpox and similar viruses (such as monkeypox) in animal trials.

Experts APM Research Lab spoke with believe TPOXX should have been widely available at major hospitals, reproductive health clinics, sexual health clinics and other public health clinics early on in the monkeypox outbreak.

“Everyone should be getting this,” Morse said. “Its safety profile is known. How can we approve a vaccine for monkeypox when it's never been tested against monkeypox and not approve tecovirimat? It’s inconsistent.”

While a small portion of individuals received the antiviral through clinical trials, the majority received it through the CDC’s expanded access Investigational New Drug protocol (ea-IND), which initially required medical providers to fill out hundreds of pages of documents for each course of TPOXX treatment. This lengthy process, experts say, was a barrier to treatment for many who were experiencing painful monkeypox symptoms.

“If something is approved by the FDA, a physician can prescribe it off label, which means that a physician can prescribe any approved drug for something else. And they often do based on their clinical judgment,” said Morse. “That's not true of this drug, even though it was approved by the FDA. It's considered an investigational drug for monkeypox, which I don't understand at all.”

Despite bureaucratic hurdles, cities and municipalities still applied to receive TPOXX and over time CDC reduced the paperwork required for providers to prescribe the treatment. Recent preliminary data from CDC shows at least 4,500 people have received the antiviral this year.

On July 27th, HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra seemed to praise his agency's response to the outbreak, saying in a statement, “Within days of the first U.S. case, we activated a multi-pronged response, significantly increasing vaccine supply and distribution, expanding access to tests, making treatments available for free, and educating the public on steps to reduce risk of infection.”

But public health experts and scholars disagree with the glowing review the government has for itself.

“The idea that they got ahead and did everything they could is just a lie,” said Kenyon Farrow, an LGBTQ+ activist and writer who says his organization, PrEP 4 All, successfully pushed HHS and FDA to get more Jynneos vaccines into the country. “They didn’t do everything they could until they were forced to.”

Farrow recalled a meeting with HHS in June, in which he told the federal agency, "There are several million doses of the Jynneos vaccine sitting in Copenhagen and they haven’t been moved while cases are spreading. We’re at the start of Pride season and the majority of cases have been identified in gay and bisexual men. So do something!”

Farrow’s accounting of events is supported by The New York Times, which reported that HHS failed to order Jynneos vaccines early enough from Bavarian Nordic—the only manufacturer in the world that makes this vaccine.

Anti-LGBTQ+ bias played a role in how the federal government responded to the outbreak, said Farrow.

“This is a way in which homophobia shows up in the world. Had we started seeing monkeypox cases in March, and it had gotten into the white Spring Break crowd in Florida, it would have been a different scenario,” Farrow stated. “They would have moved much faster, and you can’t convince me otherwise.”

Other experts also blame the severity of the outbreak on the federal government's failure to act quickly and learn from the mistakes of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“They repeated the same testing mistakes that they did with COVID in that they restricted initial testing to CDC-affiliated labs only, which were unable to cope with demand and added unnecessary layers of bureaucracy to getting a test,” Adalja said.

Adalja also took issue with HHS’s policy of shipping vaccines and antivirals to only five locations within each state, a policy which he says lacks consideration for where health resources are most needed during an outbreak. From these locations, states are responsible for moving federally distributed shipments closer to patients that need them—a process that can cost precious time and resources.

“There really needs to be a wholesale evaluation of how the government responds to infectious disease emergencies,” Adalja said. “Because it’s clearly not up to par.”

“This is a virus that's been known to science since the 1950s, for which we have off the shelf vaccines, off the shelf antivirals, off the shelf tests, and which isn't very contagious. And yet they screwed it up on the heels of COVID-19 and that's not very confidence building,” Adalja added.

Other public health experts also expressed frustration with how the administration dealt with the emerging threat.

In an op-ed written for The Hill in August, former U.S. Assistant Surgeon General, Susan Blumenthal, and professor of Global Health Law at Georgetown University, Lawrence Gostin, said the U.S. public health system “lacks coordination and technological innovation,” and is “fragmented.” They also criticized the administration's "flawed response" to the monkeypox outbreak—specifically its slowness in declaring the national outbreak a federal emergency and for the inaccessibility of vaccines and testing.

Even CDC Director, Dr. Rochelle Walensky, herself said the federal health organization failed in responding to the monkeypox outbreak and the COVID-19 pandemic. In an internal email to the CDC, Walensky announced that she would be restructuring the federal health agency to act more quickly in disseminating and acting upon potentially life-saving information and data.

The U.S. government policy of hoarding of Jynneos vaccines also left the U.S. population and the globe vulnerable to this outbreak, experts said.

“The fact that we're in this situation now is the result of shortsightedness and an unwillingness to use expiring monkeypox vaccine doses in the most impactful way.” Adalja stated. He added that before the vaccines doses expired, they should have been shared with other countries facing outbreaks. “If they were going to be expiring, the best thing would've been to distribute them to countries in which monkeypox was endemic and have them vaccinate populations in countries like the DRC and Nigeria.”

With the world being more interconnected now than it ever has been, public health experts say public health strategies and resources have to be shared at an international level.

“Viruses don't respect borders,” said Dr. Wafaa El-Sadr, professor of epidemiology and medicine at Columbia Mailman School of Public Health and lead of the New York City Pandemic Response Institute. “We live in a world that is so interconnected that within a few hours, you can go from one end of a continent to another. So what happens in one country is very important for what happens in our country and vice versa, which means that there needs to be communication between countries and shared resources as well.”

CDC and HHS did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

ARE THERE RACIAL, ETHNIC & INTERNATIONAL DISPARITIES?

While cities had to make do with what little the federal government provided, experts on the intersection of race and health said many municipalities failed to equitably distribute scarce resources.

“The way implementation happens at the city, county and state level is to do what they think is the easiest thing,” Farrow said, specifically in critique of his home state of Ohio and cities like New York. “They don’t really think about equity, and we just got through this with COVID.”

For instance, New York City, which has experienced the largest citywide outbreaks in the country this year, initially rolled out its vaccination program in Chelsea—a Manhattan neighborhood that’s whiter and wealthier than the rest of the city on average.

Two weeks later, additional doses were provided in Harlem and other areas with greater numbers of non-white populations. But anecdotal evidence suggests that online appointments for vaccines were mostly booked by white men from outside areas rather than by men of color who lived in these neighborhoods, according to Duncan.

Farrow also recalled Black and Brown queer friends in Harlem telling him they couldn’t book vaccine appointments through New York City’s website and that white men from outside their neighborhood were snatching them up. Farrow said similar issues with regards to vaccine access played out in Ohio and other states around the country.

“A vaccine strategy that would deal with racial equity would mean you couldn’t just plop up a website somewhere and expect people to have equitable access to sign on or to be able to sit all day waiting to refresh a browser,” Farrow said. “You have to take the vaccines to communities.”

Other experts echoed this assessment.

“This community is very segregated. There are plenty of white gay men who only have white gay friends. And those are the people who are most plugged into the system. They find out about the vaccine and where to get it, and they tell all their friends,” Royles said. “You have this snowballing disparity that is in addition to all the structural things that were built into how the vaccines were rolled out.”

The New York City Department of Health did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

This inequitable access to vaccines has likely had an impact on the racial disparities we now see in the outbreak. During the first weeks of the U.S. outbreak (May 15 to May 29), Black men represented only 7% to 12% of all monkeypox cases in the U.S.—a percentage similar to or less than Black people’s share of the U.S. population. As the outbreak continued, Black men began representing a significantly higher proportion of cases. By the end of August, Black men represented over 35% of all new monkeypox cases. And by September’s end, that figure was 50%.

Hispanic men followed a different trajectory. Hispanic men have accounted for 30% to 35% of new monkeypox cases during most of the outbreak, but that proportion has decreased over time. By the end of September, this group accounted for less than 20% of new cases. Similarly, white men had represented anywhere from 32% to 64% of new monkeypox cases every week before June 19th. That percentage continuously decreased throughout the outbreak with 26% of new cases being among white men at the end of September.

In addition to inequitable vaccine access, there are other potential explanations for higher rates of infection in Black and Hispanic men, according to Dr. Keletso Makofane, health and human rights fellow at the FXB Center for Health & Human Rights at Harvard University.

“One explanation for this shift is that it’s a pathogen moving through the population based on contact patterns,” Makofane said. Makofane explained that the outbreak started among an affluent, whiter group of men in Western Europe before coming over to large North American cities. Because richer, white gay men tend to be more closely connected to one another sexually than they are to other groups, the outbreak could have started there and then filtered into other populations, Makofane hypothesized.

“Another explanation could be that testing was so hard to get that the people who had access to testing were richer, whiter people. As testing has expanded, different kinds of people are now accessing tests, and so it would appear that the number of cases among Black people has increased sharply whereas it’s really a matter of detected cases increasing sharply,” Makofane said. “But the one mechanism for understanding the epidemic, which is testing, is an intervention that has not been rolled out effectively or equitably from the beginning."

Beyond disparities within the United States, the continent of Africa has no access to monkeypox vaccines, even though human outbreaks began in this region.

“A large part of Africa has no access to therapeutics or vaccines because the West is trying to satisfy their needs,” Ogoina said. “We're getting to the point where infections are stabilizing and declining in the West and people are now losing interest.”

Public health experts also made comparisons to the way the COVID-19 vaccine has been hoarded by richer countries like the United States.

“We've seen with COVID-19 that unfortunately we did not act as one world,” said El-Sadr. “There were restrictions on travel, which didn't make any sense because by the time you put in the restriction, the virus is already there. There were failures to equitably share the limited supply of vaccines early on. And similarly, to this day, there is a disparity in terms of access to treatment for COVID-19 for people who suffer from severe illness.”

“With monkeypox, I think we still have the same issue. There's a limited supply of a vaccine for monkeypox as well. And these vaccines are not available at all in the African continent,” El-Sadr added.

IS MONKEYPOX COMING TO AN END? OR ARE WE LIKELY TO SEE MORE WAVES IN THE NEAR FUTURE?

The spread of the virus shows signs of slowing down considerably within the United States and Europe. According to CDC data, over 430 confirmed cases of monkeypox were being reported daily at the height of the U.S. national outbreak in early and mid-August, whereas an average of between 50 and 70 cases per day were reported in a recent CDC update for mid-October.

As for Europe, the region documented up to 2,700 cases per week at the height of their outbreak between early July and early August. By mid-October, that statistic had gone down to 161 cases per week, according to WHO data.

But there are conflicting theories for why monkeypox cases are decreasing in these areas.

“Monkeypox is going down, both in New York and globally. Why is it doing that?” Morse said. “Some people will credit the vaccine and control measures. Other people will say that it would have eventually run its course. We don’t know.”

Despite glaring racial disparities within the U.S., the decrease in cases is good news for most within the United States and in Europe overall. However, new monkeypox infections have sharply increased in the continent of Africa. Between the end of September and the beginning of October, the Central and West African regions have seen an average of 83 confirmed cases every week. This is up from an average of only 29 confirmed weekly cases as early as August, according to WHO data. (The data is skewed, however, due to issues with data collection in DRC, Nigeria and other countries in sub-Saharan Africa.)

“Even if cases are declining in the Global North, monkeypox is still a challenge and this problem has not been addressed in Africa,” Ogoina said. “Especially if it turns out to be transmitted as sexual routes predominantly, monkeypox unfortunately may turn out to be the new HIV.”

Ogoina made comparisons to the start of major HIV/AIDS outbreaks, which initially spread in communities of gay and bisexual men in the U.S., but now impact sub-Saharan Africa the most. Ogoina said the same could be true of the trajectory of this outbreak, cautioning that we are “only looking at the tip of the iceberg,” with regards to monkeypox. While there isn't scientific consensus on the matter, Ogoina said there’s evidence to suggest the monkeypox virus has already or could in the future evolve and adapt to more easily infect human hosts.

“Even the global North is not safe,” said Ogoina. But, he added, “It's still not too late for us to invest and resolve the problem for all countries.”